5 ideas for highly engaging B2B SaaS LinkedIn posts

How do you cultivate an active and engaged LinkedIn presence for your B2B SaaS product? In this blog, we’ll explore five ideas to get you started...

Stijn Hendrikse

SaaS pricing is a very broad topic – similar to how broad “SaaS marketing” is.

Historically, many SaaS companies have created pricing models on the fly.

If you consider the strategic value of pricing for your company and how it informs product and service evolution, where you invest and your go-to-market approach, the impact of price requires data-informed decision-making on your end.

A price increase is often easy to defend and there plenty of reasons to do it, but if you poorly execute and communicate a price increase, it can all fall apart.

That’s why we created this guide—to provide you with the tools and insights needed to make smarter pricing decisions and execute them effectively

What’s most important when you think about pricing strategy for your company?

You have to find a balance between profitability and a good customer experience. Pricing should not be a negative experience, it needs to help customers feel that they have a choice.

How do you make people feel like they’re in control? How do you make your customers feel that they have choices – and that they’re behind the wheel when making those choices?

Price is a great vehicle for that. It needs to be kept simple – especially when you have product-market fit and customers who really need your solution – they’re aware of the pain they have and you’ve convinced them they need to make a change. Maybe you’ve also convinced them that you’re the right solution for them – that you’re a credible partner for them to help them change.

Now that they’re ready to move forward and give you their money, you need to make it easy. Often when pricing models become too complex, they turn into hurdles for your customers to overcome, instead of enablers for them to invest in your product.

Here, we’ll discuss the evolution of pricing with three categories: cost-based, market-based and value-based pricing.

%20(1).webp?width=630&height=314&name=saas%20pricing%201%201%20(1)%20(1).webp)

Cost-based pricing is the easiest to start with, explain and calculate – it’s based on the cost it takes to develop your goods or your professional services.

To calculate cost-based pricing for your SaaS company, simply calculate how much a product takes to develop and maintain, then add a small percentage mark-up to determine what you'll charge. For example, if your software costs $100 to design, with a 30% mark-up, you can sell this for $130 to receive a 30% profit.

SaaS cost-based pricing is often the foundational model that gets things started. Over time, you’ll find that you’re leaving money on the table. That’s because the value you create isn’t directly correlated to the cost of you doing that work.

A lot of professional services sell at a ‘cost + markup’ pricing model – even after they’ve evolved into very sophisticated categories, industries and solutions. Cost-based pricers should always be challenging themselves by asking: “How can I move up in the value chain?”

There’s a middle milestone between cost-based and value-based pricing that’s difficult to avoid – market-based pricing.

To find market-based pricing, look at what’s currently available in the market, find out what your competitors are charging, and try to understand how you fit into your prospects’ existing budgets.

This can be a valuable step for collecting data and industry insights. It’s also easier for your customers to understand than a value-based pricing model, because it’s transparent for them and they can make direct comparisons between you and your competitors.

However, the downside to this model is that you might not compare well with your competitors, which puts you at risk of becoming relegated to “vendor” status, instead of being a business partner.

With market-based pricing, you don’t get to control the way your potential prospects and customers look at how you measure up against the alternatives they have. You have to follow whatever definition your category has decided is most valuable and at what price point. That’s a real challenge if you provide a service with unique attributes or differentiators. Even though your product is special, your price will be determined by the category you happen to play in.

The easiest way to describe value-based pricing is that you’re pricing something based on the outcomes of your customer’s experiences (the value you deliver). Value-based pricing is very customer-friendly, allowing you to become a partner and offers more opportunities for larger profit.

Because this SaaS pricing strategy doesn't focus on your prices (or your competitor prices), you can focus on what your target market wants from your software. If customers will pay more because they perceive more value from your offerings, you can increase your SaaS prices and generate more revenue.

It’s a very binary outcome – profitability should go up if you use value-based pricing because if it doesn’t, you’ve just proven to yourself that if you’re not able to turn the value you’re adding into your pricing model, you might not be in the right market. In other words, what you’re doing in the specific use-case might not actually be worth doing.

Finally, if you do value-based pricing, you control the narrative and how customers position what you do versus the alternatives. You pick the positioning vectors you want to be measured against that determine what value is and what they’re willing to pay.

Controlling that messaging and positioning is extremely powerful because it will keep you away from being a price fighter or commoditized in conversations you have with your prospects.

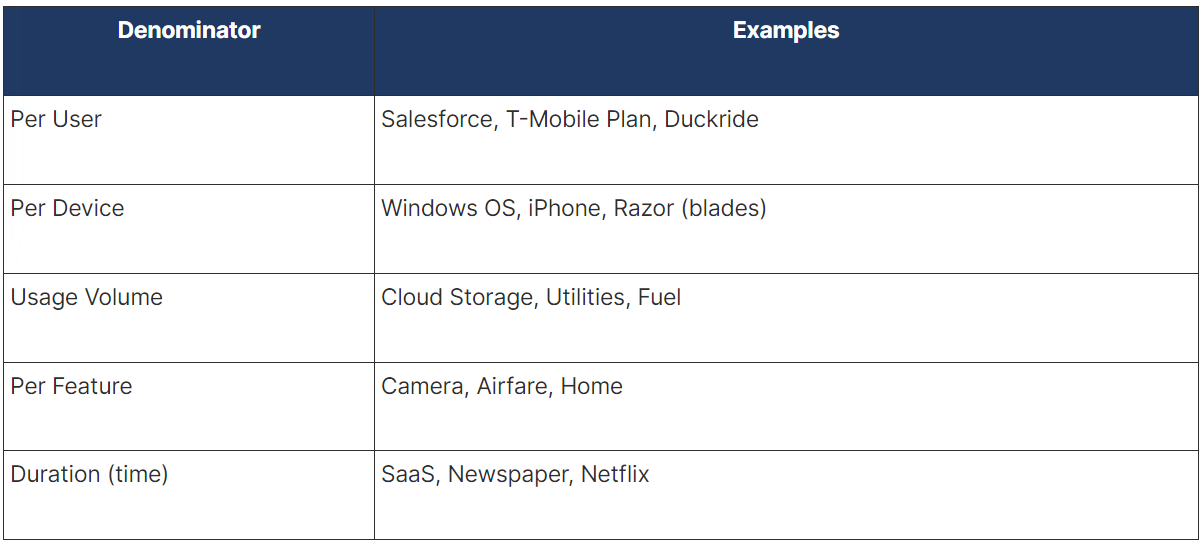

When you think of value-based pricing, one of the things you start with is the unit and pricing denominator that makes most sense for your category, what you bring, and what you sell. How do you think your customers will measure the value they get?

The denominators here are applicable to many industries:

Also known as per-seat pricing, this is the most adopted SaaS pricing model largely attributed to simplicity. Because per-user pricing makes it easy for SaaS customers to understand what they'll be paying for, it helps both users and SaaS companies anticipate their costs and revenue.

Great examples of per-user pricing are CRMs (like Salesforce) or cell phones - it’s not based on how long you use it or how much you get out of it. It’s based on the users, or profiles, that access it.

While simplicity is a leading benefit here, this pricing model also allows you to scale revenue as adoption grows across the marketplace and within organizations. As more users onboard to your software, the more revenue you'll see.

One downside of this saas pricing strategy is the additional barriers to adoption. By charging per user, this adds friction that prevents users from trying and subscribing to your products. This pricing strategy also encourages users to share passwords, ultimately limiting your company's revenue.

Per device pricing is very common; when you think of buying your phone, it comes with an operating system and that’s what you pay for per phone.

If you’re paying for a razor, which the industry is trying to turn into more of a business subscription model (like a lot of consumables), the fundamental pricing model is per device because when you go to amazon and buy razor blades, you’re still counting the price per unit, regardless of subscription or transactional.

Per-device SaaS pricing is easy to scale up and down to your customers' needs, and clients can pick and chose what they pay for.

It's hard to find the 'right' price when charging per device. This can lead to overpricing clients that need less support, emphasizes price over the value they're receiving, and often shifts the burden to their in-house support team.

Also known as 'Pay-as-you-go,' this SaaS pricing model directly relates to the cost of a SaaS product's usage. Pricing by usage volume is just what it sounds like -- you’re paying for the quantity you use.

If you fill up your car, you’re paying for the amount of gas you use. There’s a little of feature differentiation, but not much. Other examples of these are cloud storage, utilities, etc.

SaaS usage volume pricing is more popular within SaaS infrastructure and platform providers, such as Amazon Web Services (AWS). Their customers pay depending on API requests, data used, transactions processed, and other KPIs within their software.

This allows SaaS companies to scale their revenues alongside usage, reduce barriers to use, and accommodates for the heaviest users of the SaaS product.

Usage-based pricing is disconnected from the value-based pricing model as it's tied to what users are doing, not the outcomes you're driving. Usage-based pricing also poses challenges when SaaS companies forecast their revenues and profits, and also makes anticipating customer costs harder.

If you buy a camera or a home, how many bedrooms, bathrooms, acres of land, etc. However, there can be intersections in pricing strategy with this metric. For example, airfare is interesting because although you also pay per ticket (or seat) on an airplane, that’s not how the pricing structure is.

Here, the pricing structure is based on features of your flight - how much luggage can you bring on, where are you sitting, leg room, etc. If you buy a house, the pricing of this will depend on the number of bathrooms, bedrooms, square feet and acreage -- so it’s also a per feature pricing model.

Per-feature pricing is often displayed through pricing tiers, and provides strong incentives to upgrade to unlock additional functionality and benefits. This could be added data storage, upgraded user access, and more.

Another key benefit of per-feature pricing is that SaaS providers can compensate for features that require more resources and investment than others. If one feature costs far more to support than the basic features, SaaS companies should consider using per-feature SaaS pricing that reflects the value of what your team is providing.

If done wrong, per-feature pricing can discourage adoption and ultimately limit your growth. It's hard to determine what features your users will care about and pay for, and critical features can often be placed in the lower or higher end of your pricing tiers. Make sure you perform enough market research to determine what features your buyers value and will pay for.

The last pricing dimension, duration, is tricky because you don’t necessarily choose this. It’s something that happens to the industry you’re in, but there are business models that are purely based on duration.

Think about your streaming service subscription -- some of these vendors (Netflix, Hulu, etc) choose not to have feature differentiation and simply sell excess that are based on Netflix and sell excess content. By doing this, you’re paying for a month (or year) of service, regardless of how much or little you use it.

When users pay for one month or year of using your product, ARR and cash flow can increase if they're using features that don't use a lot of your resources.

Some users may take advantage of this pricing strategy, especially if specific features and benefits don't correlate to your input or resources. If you're using time-based SaaS pricing, make sure you carefully calculate how much a subscription will cost in-house.

If the product you sell has a tendency to be used by a few users first and then grow over time, maybe per user pricing might be the best way for you to maximize lifetime value.

For other products and services, it might be easiest to maximize lifetime value with a per user pricing denominator.

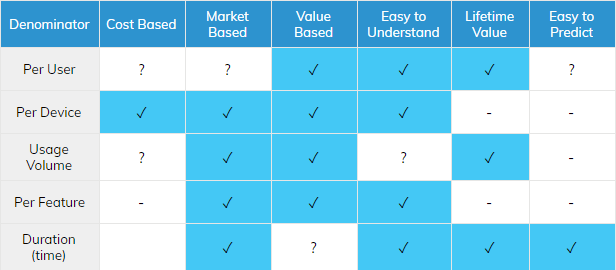

With financial modeling in mind, think about which of these will be easier to predict (consumption levels, growth over time) than other dimensions. Again, this is all very dependent on your industry.

When you pick your pricing dimensions, make sure you and your customer understand the dimension in entirety -- that means you have to be able to measure it.

Follow these best practices for an optimized pricing strategy:

Pick a pricing model that is easy to measure. If you pick a dimension that is hard to enforce, it might not be the best dimension to base your product pricing on. For example, if you decide to use per-user pricing, make sure you can actually measure how many people use your product or service.

No matter which dimension you choose, make sure you're on the path to value-based pricing. What you've probably noticed is that most of these dimensions are not going to be used in isolation. There's probably one primary pricing dimension that really drives revenue growth from a single customer or a single user. This is called Average Revenue per Unit (ARPU), and you can pick the “unit” as the user, the device, etc.

Usually, pricing uses a combination of dimensions. Here are some common combinations of pricing dimensions:

If you think of a subscription plan as a piece of software, it’s usually a combination of the duration (you pay per month, per year, etc) and you typically pay per user. Then, there is often also a feature differentiation where you have multiple plans to pick from. Fuel is another good example of a combination of the usage and feature combination. The type of fuel that you put in your car in addition to volume determines pricing here.

You can’t combine too many different dimensions in a combination. I think three is really the max because any more than that and it’ll be confusing for your customers and you.

If you think of these three B2B SaaS pricing models in the above examples (duration per user and per feature, usage and per feature, per device and per feature), all three have in common that per feature -- it’s a common dimension that is always applied. This is typical for the more innovative industries and complex products and services. Features are typically a part of how you price.

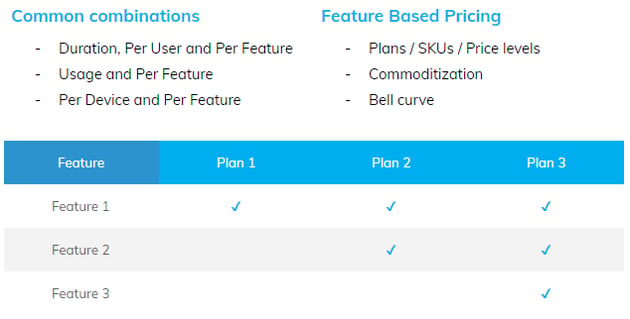

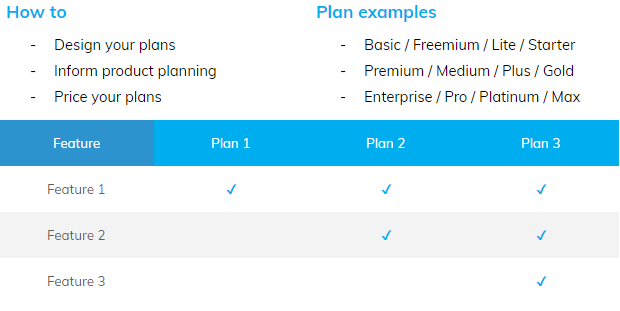

Now, we’ll dive into per-feature pricing a little bit more because coming up with pricing plans and strategies for these other dimensions is a little more straightforward than the per-user-based plan or usage-based plan.

The per feature part is harder to design. What you often will find is something like the table below, where you see that you have multiple plans and price levels that align with the capabilities or features that you're able to then use as a customer.

How do you do that? How do you come up with your feature-based pricing structure? It's really important that you do this holistically because it can also help you inform your product planning. And of course, it will help you figure out where the pricing levels should lie.

Some examples of what you would see in these columns, basic, premium, professional, silver, gold, platinum, basic, medium, pro, enterprise is often also used, depending on what type of pricing model you're doing and what type of industry, what category.

If you’re selling software, it is very hard to do any form of pricing unless you understand what benefits are being accrued from these features. You have to do the hard work and turn your language for the capabilities that you offer, the features that you sell into, and what it enables. Once you understand the impact of those capabilities and benefits, you can start thinking about how to measure it, and how to turn that into value-based pricing.

Mixing different prices dimensions can be very powerful as long as you can keep the complexity under control. But the time commitment plays a role in pricing incentives and pricing plans, too. That’s the balance between choice, cash and churn.

Churn is mostly applicable to subscription business models -- people really value choice and they put a price on that. The fact that they can opt out next month versus next year has value. Sometimes it's a 10% price increase and sometimes it's 30% -- it all depends a little on how important it is that they have access to what you have to offer. This is why choice is a valuable element and you have to figure out what the real cash value of that is.

Pricing starts with an understanding of what you're actually selling and features are a great way to organize thinking through your product.

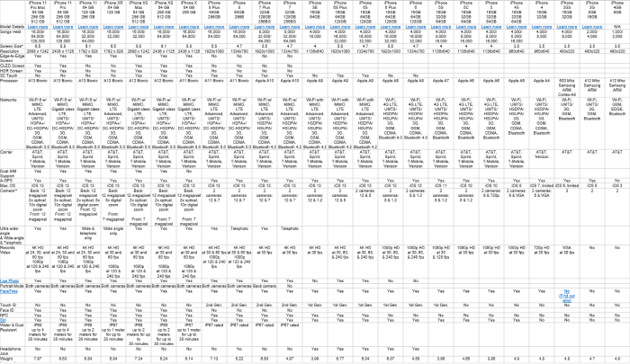

This is the lineup of all the iPhones since they came to market:

When you have a complex product evolution and your product changes over time, it becomes richer as you enable it with new innovation. This means you constantly have to figure out how to simplify your presentation and the features and capabilities and use language that communicates benefits that make it easy for people to pick what they need. As you can see from the table above, some features also get taken away over time. For example, the headphone jack disappeared at some point.

And even after the complicated features were removed, there were still 20 rows of capabilities that could inform a certain pricing structure and certain positioning approach. This is why it’s really important to gain understanding and control over what capabilities your service or product delivers.

So, how do you organize what you do? What are the benefits that you bring into bear in a way that can help you make those decisions? What are you going to use to position your product and drive your pricing decisions? That’s where the feature matrix really helps.

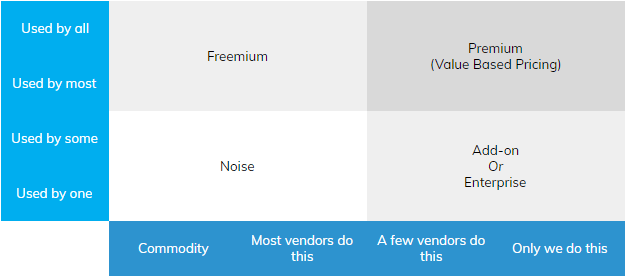

The feature matrix gives you a grasp of how your features and capabilities align with what most of your anticipated the market is looking for, and how unique those things are. This is an exercise that we recommend for anybody who's selling a relatively complex solution.

The Vertical Axis measures how each feature is relevant to the largest audience. This axis measures how many of these features are actually used by the majority of potential customers or how many things are used by everyone. Here, talk about how many customers or market members need this capability or feature.

The Horizontal Axis, on the other hand, measures how many of these features are common or unique to your product or service offerings. Take a really hard look at how special your offerings actually are. Is that thing, capability, or feature really unique? If it's something that ONLY you can do, then that feature would go more to the right on the horizontal axis. But when it's a relatively commoditized capability, it would be closer to the left. Things that some, but not all of your competitors do may be somewhere in that middle tier.

Now, let's use an example: A Smartphone.

.webp?width=626&height=312&name=saas%20pricing%20strategy3%201%20(1).webp)

The capability of making a phone call, checking email or accessing a calendar would probably fall on the upper left of the matrix. It's not something that's going to be very unique. It's completely commoditized but everybody needs it. It's probably something that almost everybody can do now, every phone vendor.

Apple’s retina display may be used by everybody and is also a real differentiator that would be something people would pay money for. The features in the blue quadrant are your differentiators AND matter most to your audience. That’s why awareness of the blue box is critical to your company’s success.

There will also be things that don't make it to the blue box, but they're still very valuable for a smaller group of customers. You still want to sell and market those features, but maybe not to everyone. You may not put that on the front page of your website because you also want to keep your messaging simple.

Now you can think about how to price products in this three-tier model (good, better, best)?

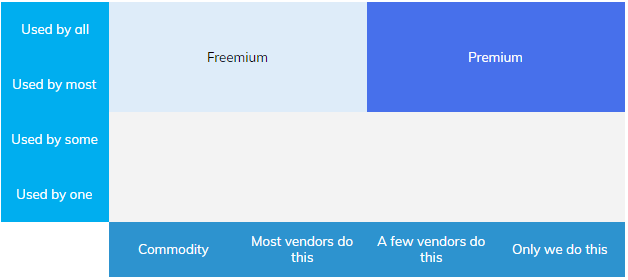

There are three quadrants that would end up being candidates for your plans: the freemium, premium and add-on quadrants.

You could have a lineup of products that have capabilities that are needed by every customer, but they're not that differentiators, so maybe give it away for free. It's a great way for you to get the volume to attract people and let them familiarize themselves with your product without asking for payment yet. This is what we call The Freemium. If you have a way to upsell your product from the freemium plan into the Premium Plan, where you really want to create the profitable part of your value proposition, then maybe the freemium quadrant is the way to get them there.

There might be a few customers who are willing to pay more for a specific capability you have and you turn that into an Add-On. If you decide that 10% of your customers need enterprise features, that becomes the new red box.

The lower left quadrant is the grouping of features that are not really relevant for anybody and they're not differentiated. So, when you assess what you have in your website, sales materials or marketing collateral, if you do this exercise and you find things that are on the lower left quadrant, remove those from your messaging, your website, etc and clean your value proposition and messaging up.

Now, you have the foundation to think about where you want to put your product’s capabilities and which plan will drive value-based pricing.

When thinking about a value-based pricing model, first consider if you believe that the unique features are driving value for a large amount of customers. Then, think about the output of the value you create, how you measure the tangible results, and the net impact.

.webp?width=629&height=278&name=saas%20pricing%205%20(2).webp)

Now, you can think about product planning. If you believe that what's in the upper right blue quadrant is what sets you apart, make sure that you keep filling that quadrant.

In the lower right quadrant, this is where you build new capabilities that may not yet be used (or not yet relevant) for a large group of customers. This is where you innovate and test features with a smaller group of customers and, as those things catch on and become more popular, it might make it into your premium pricing plan in the blue quadrant.

But keep in mind that those things will get commoditized -- your competitors will copy what you do (or they will claim they do so) so you need to figure out how to keep filling that blue quadrant with new capabilities.

Of course, this is going to differ from one industry to the next. If you're running a SaaS business, it is critical that you keep filling the blue quadrant because when you're literally asking people to pay you again tomorrow and you need to add value again tomorrow. That's the handshake you do with your customers, especially when you want them to pay a year in advance.

What else do you think about? You can do the DIY Feature Matrix in three steps:

Below is an example of the matrix that shows the core capabilities of a software solution normalized across these four quadrants. This helps us determine features and elements of the software are most powerful to position and communicate with your market.

These elements of the upper right blue quadrant are the things that we can use to model our pricing structure around.

%20(1).webp?width=700&height=425&name=saas%20pricing%20strategy%205%201%20(1)%20(1).webp)

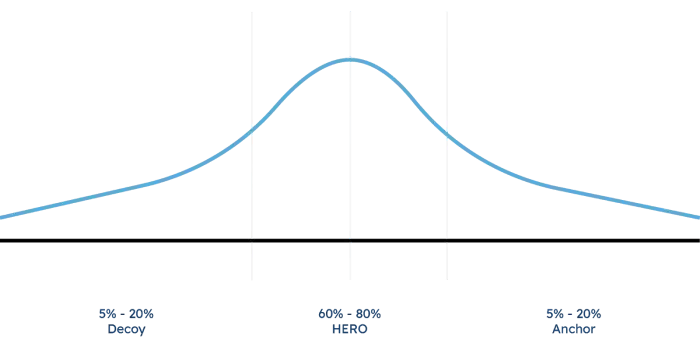

If you think of your customer population as a bell curve with a normal distribution, you want to optimize your price plan so that about 70% of your customers fall in the upper right blue quadrant.

This way, the anticipated amount of people that will pay you for your premium plan, for the core of your value proposition, will be the largest piece of the bell curve. This way, you are servicing a large population with differentiated features so that people will gladly pay for that.

Then, the rest of your customers are either on the left or the right side of this distribution -- maybe 10, 15 or 20%. This way, you can organize how many features you need to offer to the middle band to satisfy 70% of your customer base’s needs. What do you have to offer for 70% of your anticipated market to pick that central hero skew? We call it the hero skew because the hero is your ideal customer profile.

What is the feature set that you would put in that upper right blue quadrant so that 70% of your customers would fall there?

There’s a reason why three-tier pricing plans work well -- you can now have both an anchor and a decoy.

On home improvement shows when someone is looking for a new house, the realtors always show their clients the “anchor” house first -- it’s too expensive, outside of the budget, but it shows the features and amenities they love.

Then, they often go to the Hero -- this is more attainable, realistic and still checks all of the boxes. Then, they go to the Decoy-- that's basically not what they want. They can afford it, but it's not necessarily what they need and they end up picking the middle road.

This is just like pricing plans for SaaS. Having an anchor is very important. It doesn't have to be artificial though. It could easily be a part of the market that you really service very special capabilities that are only relevant for a smaller group of customers.

The same goes for the decoy. This isn’t just a psychological trick -- it could be your freemium plan, something that really helps you keep your market share and then have an upsell path and to help get people move from your freemium to premium.

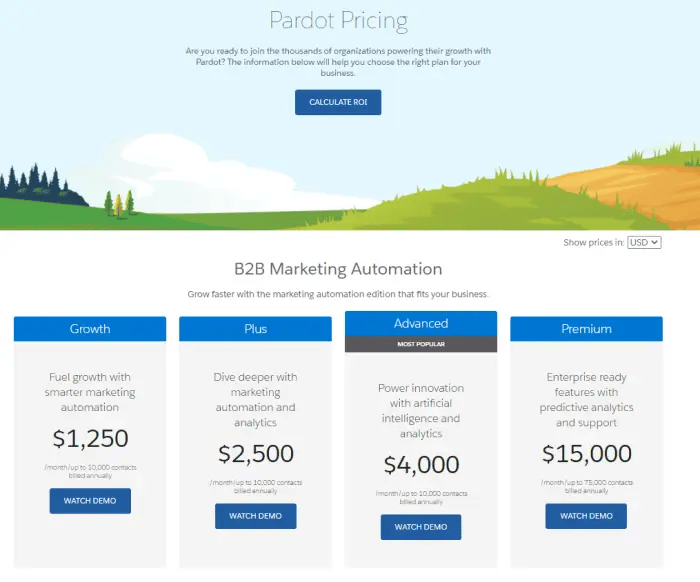

On Salesforce Pardot's pricing page, you can see four pricing tiers and their billing information. While the 'Premium' package is the Anchor and the 'Growth' and 'Plus' are the Decoys, they highlight the 'Advanced' package as their most popular--the Hero:

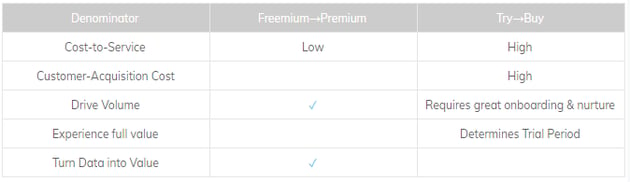

Freemiums offer a path for people to get going with a low barrier of entry and a price they can afford. Then, they can test if they need this value proposition and decide to upgrade or not. The problem with a freemium-premium model is that your customers will not experience your full value proposition.

Don’t forget that when you have a freemium plan, you need to have a low-cost-to-service, especially when you're a SaaS business or a service business. Customer acquisition cost (CAC) is important, but cost-to-service is far more important, especially when you offer a freemium plan.

On the other hand, a try-buy model still gets people in the door, and at a low price level. A real trial would be free for a specified time period, but you let them experience the full value proposition and then allow them to convert to becoming a paying customer.

A try-buy model works well if your cost-to-service is relatively high, and you cannot afford a freemium model. Try-buy also works well if your customer acquisition cost is pretty high. It's a way to get people in the door maybe a little cheaper.

It's important that you think of the freemium and the try-buy as different approaches. They can be combined, but if someone is in a trial program and they don't convert to buy, they could fall back into a freemium plan that you may only offer to people who went through your trial.

You need to prepare for onboarding and nurture campaigns when you do try-buy because the trial period of a try-buy model is determined by how long it takes people to get going, to get onboard, and realize the value they need to recognize before they're willing to pay you.

Whether a trial period is five days, five weeks or five months, consider how long it takes people to get going and experience the value that will make them willing to pay full price. It’s your job to make that the onboarding period as short as possible and letting them use the products quickly with maximum results.

Now that we’ve covered pricing plans and structures, the foundation of your pricing strategy and how you model your value proposition, sooner or later you're going to decide that you need to change your pricing.

Even though companies know they can raise prices, the basics of communication, cadence and organizing the mechanics is the tricky part - but it's worth doing so. It's just like saving money by doing your taxes well. It's the easiest way to get more profitability.

It's not a question of “can you raise prices by 10%”, it's more about how you raise prices by 10%. If your audience is aware of the basic laws of economics, then they’re aware of price inflation, and you’re also adding value over time through new capabilities and features.

Still, it’s hard to increase pricing. Not because the price itself is hard to raise, but because it's hard to communicate and implement well. There are a lot of details to manage, like grandfathering in former customers with certain loyalty principles, so SaaS price increases are typically lagging behind what the market can bear.

Everyone has an opportunity to raise prices, but not everyone knows how to execute this well in order to minimize collateral damage.

Remind your customers about the results from using your services and review the new capabilities you’ve added since they signed up.

Make sure they feel good about the price change -- you can provide them the choice to lock in their current price and prepay. And when you get a prepayment maybe in return, they feel they had a choice and could opt into something that you provided.

You can also allow them to switch to another plan with different value-added features. Remember to communicate clearly why you're increasing prices, and explain the benefits and value you're providing to your clients.

But how do you actually derive a value, whether you have to raise prices or not? Make it a benefit and reward loyalty! If you raise prices, but you allow your existing customers to be grandfathered in to receive special treatment, it could actually increase the satisfaction of some customers over the long-term rather than driving dissatisfaction. Keep in mind that this only works if you communicate well, if people can organically make the decision and have time to consider all of their options.

Don't do this in a week -- maybe there’s a multi-month period that you use to communicate to your customers before those changes in pricing go into effect.

Make sure all stakeholders, business partners, and prospects in the pipeline are getting the same messages. Don’t blame anybody, don’t talk about inflation as a scapegoat or use one specific reason why you’re raising prices -- there are many other good reasons to do so.

If you have relationships with your customers and prospects, you may want to explain this over the phone instead of email.

When you are providing a service like software, your product is not a perpetual license sold in a new financial construct. Think about SaaS business as providing a service with a new net value every day someone uses it.

This is why your product and service must be more than just the features they use. You have to sell the value of the data that you have, the value of your team, the experience with the customer success team, and how you take your customers by the hands and become a real partner.

It's not necessarily transactional products that become more expensive over time, just like your dentist and doctor's office visits become more expensive over time. When you’re thinking about the SaaS pricing model, you need to prioritize constant innovation. Focus on filling that upper right blue quadrant with new capabilities that are unique. This way, you have a very good reason to keep your prices going up overtime at a regular interval.

Let's say you sell a house with unique features and you're in Seattle. 20 years ago, most houses didn't have air conditioning. So, some houses would have that feature of air conditioning, but that's not necessarily the way you would sell it. You would sell it as a benefit. The benefit of air conditioning allows you to gain more pleasure at home, do business there, feel comfortable, etc.

There are all kinds of other examples where you have to communicate a feature as a benefit. If you don't do this, it becomes very hard to communicate the value of the product and explain price increases (or the reason something has to be priced according to value-based pricing).

Internally, it’s easiest to use features and capabilities to describe what you do, but when you’re communicating with your audience, explain the benefits your audience gets out of them.

Price increases are an easy way to drive product profitability, but make sure your client discounting is under control.

If you have a larger sales team, it's important to understand the empowerment matrix -- Who is allowed to give out what type of discounts, and in exchange for what? Never give a discount away for nothing - always ask yourself “What am I getting in return?” Maybe you’re getting a prepayment or commitment to a case study.

Discounts go further than just the price. This also includes special payment terms or legal exposure, different liability limits, etc. This is why it’s crucial you have a strong framework, even if it only includes a few people that determines who is able to give away what.

Even if you have a great pricing strategy, you can enforce it and you have a pricing model that actually works. All of these positives can be completely negated if you have people giving away things at the back end that you don't really want to happen.

There's a logical and scientific way to almost think about discounting, especially when you have products in a SaaS or subscription business model.

You might offer a discount for a few reasons, all of which save you money in the long term:

Prepaid discounts could be easily warranted by any of these three bullets, but one of those must be the reason you offer it. If you offer a discount for other reasons, you may leave money on the table because you're telling people to pay you less than they would have otherwise paid.

If a commitment includes things like getting an auto-payment setup or inputting credit card details, turning this into an opt-in where people have to renew every year (or every month) into an opt-out where they have to actively opt-out of your payment structure is worth the discount.

Just make sure you can enforce this.

When you deliver a service that's not recoverable, like human labor, it throws a wrench into these discounts.

Make sure you understand what your pricing foundation is and why it is the right foundation to move people along some kind of price curve, as per user, per device, etc.

Then, do a feature matrix exercise because that's the dimension that you really control. It's the number of users who use your product, the amount of usage etc.

They may seem pretty straightforward, but how you categorize what capabilities and features people get in one pricing plan versus the next is really where you have a lot of control.

Figure out how you service the largest population of your customers in the middle of that bell curve with the part of your product set and the feature set that is most profitable for you. That allows you to transition into value-based pricing because you know which features can differentiate you.

That allows you to think of the value that you bring and how that turns into the lifetime value of your customers – what do they pay you over time minus the cost of service – gets you to your profitability outlook so you can think about what you’re willing to discount and remain profitable or maximize the profitability over time.

There’s nothing wrong with raising your prices once a year. If you haven't done so this year, and the year just started, try raising your prices. The fallout that people think they'll get is usually negligible and the upside is always there, even if only a few people end up paying you more.

Developing a winning B2B SaaS pricing strategy requires expertise, precision, and a deep understanding of your market. That’s where Kalungi comes in.

Kalungi is a full-service B2B SaaS marketing agency. We've helped over 100 companies achieve significant ARR expansion, customer growth, and market leadership.

Our approach combines strategic leadership with hands-on execution. Each engagement is led by a seasoned CMO, supported by a flexible team of SaaS marketing professionals, and driven by Kalungi’s proven T2D3 playbook. From pricing models and positioning to multi-channel campaigns, we ensure every element of your strategy works in harmony to drive measurable results.

Ready to optimize your pricing strategy and accelerate your growth? Schedule a discovery call with Kalungi today.

How do you cultivate an active and engaged LinkedIn presence for your B2B SaaS product? In this blog, we’ll explore five ideas to get you started...

Find the CRM that provides the interconnectivity you need to maximize your customer journey and unlock your B2B SaaS growth.

Should your B2B company hire a Fractional CMO? Learn why they’re valuable for SaaS startups & how to determine if they’re the right fit for your...